Art for a World in Shambles

Abstract expressionism was an American post–World War II art movement that can be thought of a bridge between modern and postmodern painting (around 1960). Although it is true that spontaneity or the impression of spontaneity characterized many of the abstract expressionists’ works, in reality most of these paintings involved careful planning, especially since their large size demanded it. In many instances, abstract art implied the expression of ideas that concern the spiritual, the unconscious, and the mind.

Barnett Newman wrote:

We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world destroyed by a great depression and a fierce World War, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of paintings that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello. Barnett Newman, "Response to the Reverend Thomas F. Mathews," in Revelation, Place and Symbol (Journal of the First Congress on Religion, Architecture and the Visual Arts), 1969.

Although distinguished by individual styles, the Abstract Expressionists shared common artistic and intellectual interests. While not expressly political, most of the artists held strong convictions based on Marxist ideas of social and economic equality. Many had benefited directly from employment in the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. There, they found influences in Regionalist styles of American artists such as Thomas Hart Benton, as well as the Socialist Realism of Mexican muralists including Diego Rivera and José Orozco.

The growth of Fascism in Europe had brought a wave of immigrant artists to the United States in the 1930s, which gave Americans greater access to ideas and practices of European Modernism. They sought training at the school founded by German painter Hans Hoffmann, and from Josef Albers, who left the Bauhaus in 1933 to teach at the experimental Black Mountain College in North Carolina, and later at Yale University. This European presence made clear the formal innovations of Cubism, as well as the psychological undertones and automatic painting techniques of Surrealism.

Whereas Surrealism had found inspiration in the theories of Sigmund Freud, the Abstract Expressionists looked more to the Swiss psychologist Carl Jung and his explanations of primitive archetypes that were a part of our collective human experience. They also gravitated toward Existentialist philosophy, made popular by European intellectuals such as Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre.

Given the atrocities of World War II, Existentialism appealed to the Abstract Expressionists. Sartre’s position that an individual’s actions might give life meaning suggested the importance of the artist’s creative process. Through the artist’s physical struggle with his materials, a painting itself might ultimately come to serve as a lasting mark of one’s existence. Each of the artists involved with Abstract Expressionism eventually developed an individual style that can be easily recognized as evidence of his artistic practice and contribution.

What’s in a Name?

As the term suggests, the work was characterized by highly abstract or non-objective imagery that appeared emotionally charged with personal meaning. The artists, however, rejected these implications of the name. They insisted their subjects were not “abstract,” but rather primal images, deeply rooted in society’s collective unconscious. Their paintings did not express mere emotion. They communicated universal truths about the human condition. For these reasons, another term—the New York School, championed by the influential critic Clement Greenberg—offers a more accurate descriptor of the group, for although some eventually relocated, their distinctive aesthetic first found form in New York City.

Painters in Postwar New York City

The end of World War II was a pivotal moment in world history and by extension the history of art. Many European artists had come to America during the 1930s to escape fascist regimes, and years of warfare had left much of Europe in ruins. In this context New York City emerged as the most important cultural center in the West. In part, this was due to the presence of a diverse group of European artists like Arshile Gorky, Marcel Duchamp, Salvador Dalì, Piet Mondrian, and Max Ernst, and the influential German teachers Josef Albers and Hans Hofmann (see also Black Mountain College). American artists’ exposure to European modernist movements also resulted from the founding of the Museum of Modern Art (1929), the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (later the Guggenheim Museum, 1939), and galleries that dealt in modern art, such as Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of this Century (1941). Both Americans and European expatriates joined American Abstract Artists, a group that advanced abstract art in America through exhibitions, lectures, and publications.

These institutions and the art patrons affiliated with them actively promoted the work of New York City artists. During the 1940s and ’50s, the scene was dominated by Abstract Expressionists, a group of loosely affiliated painters participating in the first truly American modernist movement. Abstract Expressionism’s influences were diverse: the murals of the Federal Art Project, in which many of the painters had participated, various European abstract movements, like De Stijl, and especially Surrealism, with its emphasis on the unconscious mind that paralleled Abstract Expressionists’ focus on the artist’s psyche and spontaneous technique. Abstract Expressionist painters rejected representational forms, seeking an art that communicated on a monumental scale the artist’s inner state in a universal visual language.

The rise of the New York School reflects the broader cultural context of the mid-twentieth century, especially the shift away from Europe as the center of intellectual and artistic innovation in the West. Much of Abstraction Expressionism’s significance stems from its status as the first American visual art movement to gain international acclaim.

What Does it Look Like?

Although Abstract Expressionism informed the sculpture of David Smith and Aaron Siskind’s photography, the movement is most closely linked to painting. Most Abstract Expressionist paintings are large scale, include non-objective imagery, lack a clear focal point, and show visible signs of the artist’s working process, but these characteristics are not consistent in every example.

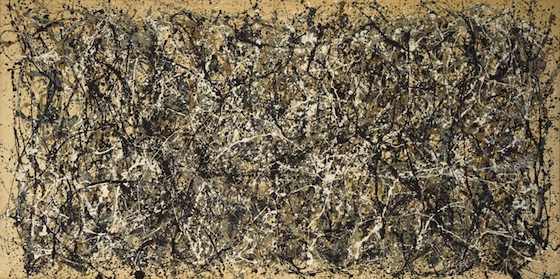

Abstract Expressionist painters fall into two broad groups: those who focused on a gestural application of paint, and those who used large areas of colour as the basis of their compositions. The leading figures of the first group were Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning, Lee Krasner, and above all Jackson Pollock. Pollock’s innovative technique of dripping paint on canvas spread on the floor of his studio prompted critic Harold Rosenberg to coin the term action painting to describe this type of practice. Action painting arose from the understanding of the painted object as the result of artistic process, which, as the immediate expression of the artist’s identity, was the true work of art. Helen Frankenthaler also employed experimental techniques by pouring thinned pigments onto untreated canvas.

Action Painting

In the case of Willem de Kooning’s Woman I, the visible brush strokes and thickly applied pigment are typical of the “Action Painting” style of Abstract Expressionism also associated with Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. Looking at Woman I, we can easily imagine de Kooning at work, using strong slashing gestures, adding gobs of paint to create heavily built-up surfaces that could be physically worked and reworked with his brush and palette knife. De Kooning’s central image is clearly recognizable, reflecting the tradition of the female nude throughout art history. Born in the Netherlands, de Kooning was trained in the European academic tradition unlike his American colleagues. Although he produced many non-objective works throughout his career, his early background might be one factor in his frequent return to the figure.

Color Field Painting

The second branch of Abstract Expressionist painting is usually referred to as Color Field painting. Two central figures in this group were Mark Rothko, known for canvases composed of two or three soft, rectangular forms stacked vertically, and Barnett Newman, who, in contrast to Rothko, painted fields of colour with sharp edges interrupted by precise vertical stripes he called “zips” (see Vir Heroicus Sublimis, 1950–51). Through the overwhelming scale and intense colour of their canvases, Colour Field painters like Rothko and Newman revived the Romantic aesthetic of the sublime.

In contrast to the dynamic appearance of de Kooning’s art, Mark Rothko and Barnett Newman exemplify what is sometimes called the “Color Imagist” or “Color Field” style of Abstract Expressionism. These artists produced large scale, non-objective imagery as well, but their work lacks the energetic intensity and gestural quality of Action Painting.

Rothko’s mature paintings exemplify this tendency. His subtly rendered rectangles appear to float against their background. For artists like Rothko, these images were meant to encourage meditation and personal reflection. Adolph Gottlieb, writing with Rothko and Newman in 1943, explained, “We favor the simple expression of the complex thought.”Letter from Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb to Edward Alden Jewell Art Editor, New York Times, June 7, 1943.

Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis illustrates this lofty goal. In this painting, Newman relied on “zips,” vertical lines that punctuate the painted field of the background to serve a dual function. While they visually highlight the expanse of contrasting color around them, they metaphorically reflect our own presence as individuals within our potentially overwhelming surroundings. Newman’s painting evokes the eighteenth century notion of the Sublime, a philosophical concept related to spiritual understanding of humanity’s place among the greater forces of the universe.