Photography undergoes extraordinary changes in the early part of the twentieth century. This can be said of every other type of visual representation, however, but unique to photography is the transformed perception of the medium. In order to understand this change in perception and use—why photography appealed to artists by the early 1900s, and how it was incorporated into artistic practices by the 1920s—we need to start by looking back.

So what transforms the perception of photography in the early twentieth century? Social and cultural change—on a massive, unprecedented scale. Like everyone else, artists were radically affected by industrialization, political revolution, trench warfare, airplanes, talking motion pictures, radios, automobiles, and much more—and they wanted to create art that was as radical and “new” as modern life itself. If we consider the work of the Cubists and Futurists, we often think of their works in terms of simultaneity and speed, destruction and reconstruction. Dadaists, too, challenged the boundaries of traditional art with performances, poetry, installations, and photomontage that use the materials of everyday culture instead of paint, ink, canvas, or bronze.

By the early 1920s, technology becomes a vehicle of progress and change, and instills hope in many after the devastations of World War I. For avant-garde (“ahead of the crowd”) artists, photography becomes incredibly appealing for its associations with technology, the everyday, and science—precisely the reasons it was denigrated a half-century earlier. The camera’s technology of mechanical reproduction made it the fastest, most modern, and arguably, the most relevant form of visual representation in the post-WWI era. Photography, then, seemed to offer more than a new method of image-making—it offered the chance to change paradigms of vision and representation.

With August Sander’s portraits, such as Secretary at a Radio Station, Pastry Cook or Disabled Man, we see an artist attempting to document—systematically—modern types of people, as a means to understand changing notions of class, race, profession, ethnicity, and other constructs of identity. Sander transforms the practice of portraiture with these sensational, arresting images. These figures reveal as much about the German professions as they do about self-image.

Cartier-Bresson’s leaping figure in Behind the Gare St. Lazare reflects the potential for photography to capture individual moments in time—to freeze them, hold them, and recreate them. Because of his approach, Cartier-Bresson is often considered a pioneer of photojournalism. This sense of spontaneity, of accuracy, and of the ephemeral corresponded to the racing tempo of modern culture (think of factories, cars, trains, and the rapid pace of people in growing urban centers).

Umbo’s photomontage The Roving Reporter shows how modern technologies transform our perception of the world—and our ability to communicate within it. His camera-eyed, colossal observer (a real-life journalist named Egon Erwin Kisch) demonstrates photography’s ability to alter and enhance the senses. In the early twentieth-century, this medium offered a potentially transformative vision for artists, who sought new ways to see, represent, and understand the rapidly changing world around them.

Photography as Art in America

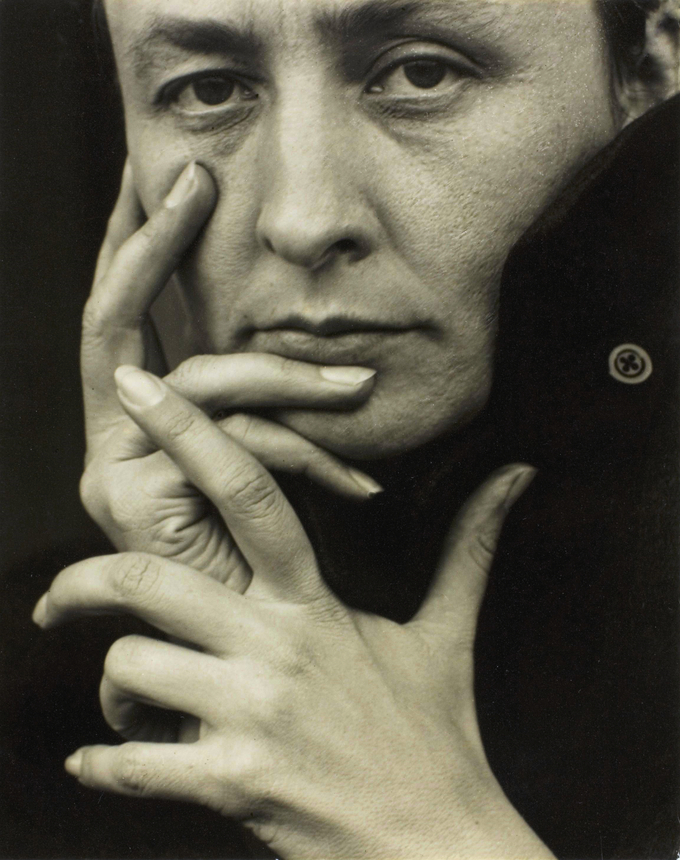

In the U.S., F. Holland Day, Ansel Adams, Alfred Stieglitz, and Edward Steichen were instrumental in making photography a fine art, and Stieglitz was especially notable in introducing it into museum collections. Until the late 1970s several genres predominated, such as nudes, portraits, and natural landscapes. Breakthrough artists in the 1970s and 80s, such as Sally Mann, Robert Mapplethorpe, Robert Farber, and Cindy Sherman, still relied heavily on such genres, although saw them with fresh eyes. Others investigated a snapshot aesthetic approach. American organizations, such as the Aperture Foundation and the Museum of Modern Art, have done much to keep photography at the forefront of the fine arts.

Photo-Secession Movement

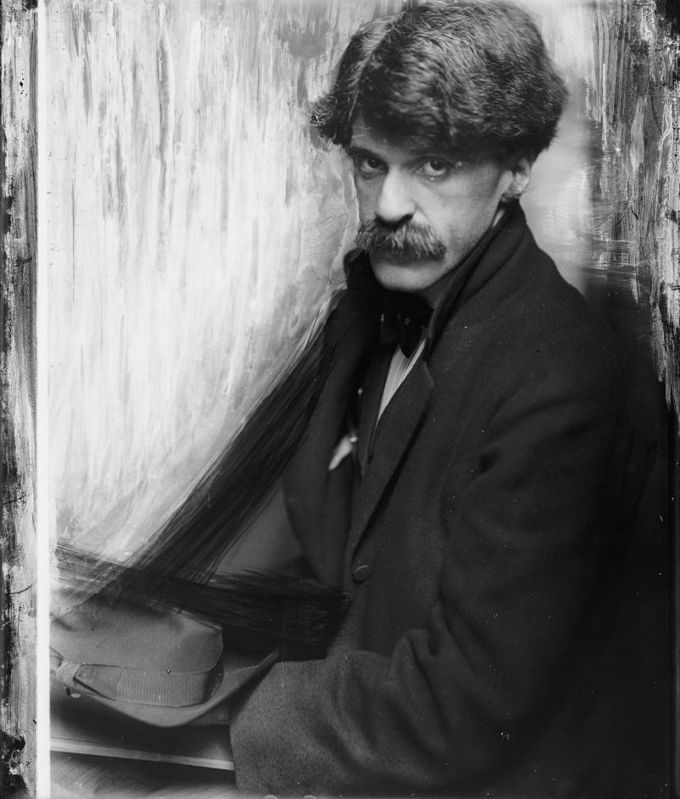

Photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) led the Photo-Secession movement, a movement that promoted photography as a fine art and sought to raise standards and awareness of art photography. The Photo-Secession movement placed the focus on the role of the photographer as an artist. It was characterized by pictorialism, in which pictures and photographic materials were manipulated to emulate the quality of paintings and etchings being produced at that time. Among the methods used were soft focus; special filters and lens coatings; burning, dodging and/or cropping in the darkroom to edit the content of the image; and alternative printing processes such as sepia toning, carbon printing, platinum printing or gum bichromate processing.

Centered in Gallery 291 in New York City from 1902–1916, membership to the Photo-Secession movement was by invitation-only and varied according to Stieglitz’s interests. The most prominent members included Edward Steichen, Clarence H. White, Gertrude Käsebier, Frank Eugene, F. Holland Day, and Alvin Langdon Coburn.

At the same time, however, photography’s use as a tool of realistic documentation mirrored the growth of American Realism in art and sculpture. Many photographers sought to capture everyday life of American people—both the wealthy and the poor—in a realistic and often gritty fashion. Lewis Hine (1874–1940) used light to illuminate the dark areas of social existence in his Pittsburgh Survey (1907), which investigated working and living conditions in Pittsburgh. He later became the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee. Paul Strand (1890–1976) created brutally direct abstractions, close-up portraits, and documented machines and cityscapes.

Precisionist Movement

Edward Weston (1886–1958) would become a leader in the Precisionist Movement, a style that functioned in direct opposition to the Photo-Secession Movement. This movement was the first true use of modernism in photography. It was characterized by sharp focus and carefully framed images. James Van Der Zee (1886–1983) was an African American photographer who became emblematic of the Harlem

Commercial Photography

Commercial photography also expanded during this time, as in the works of Edward Steichen (1879–1973). Steichen broke with Stieglitz toward the end of the Photo-Secession movement and created the first commercial image in 1919, entitled Pear and Apple. His work was featured in magazines such as Vanity Fair. Ansel Adams (1902–1984) also began his career as a commercial photographer and became widely known for his images of American landscapes.